Who Caused All this?

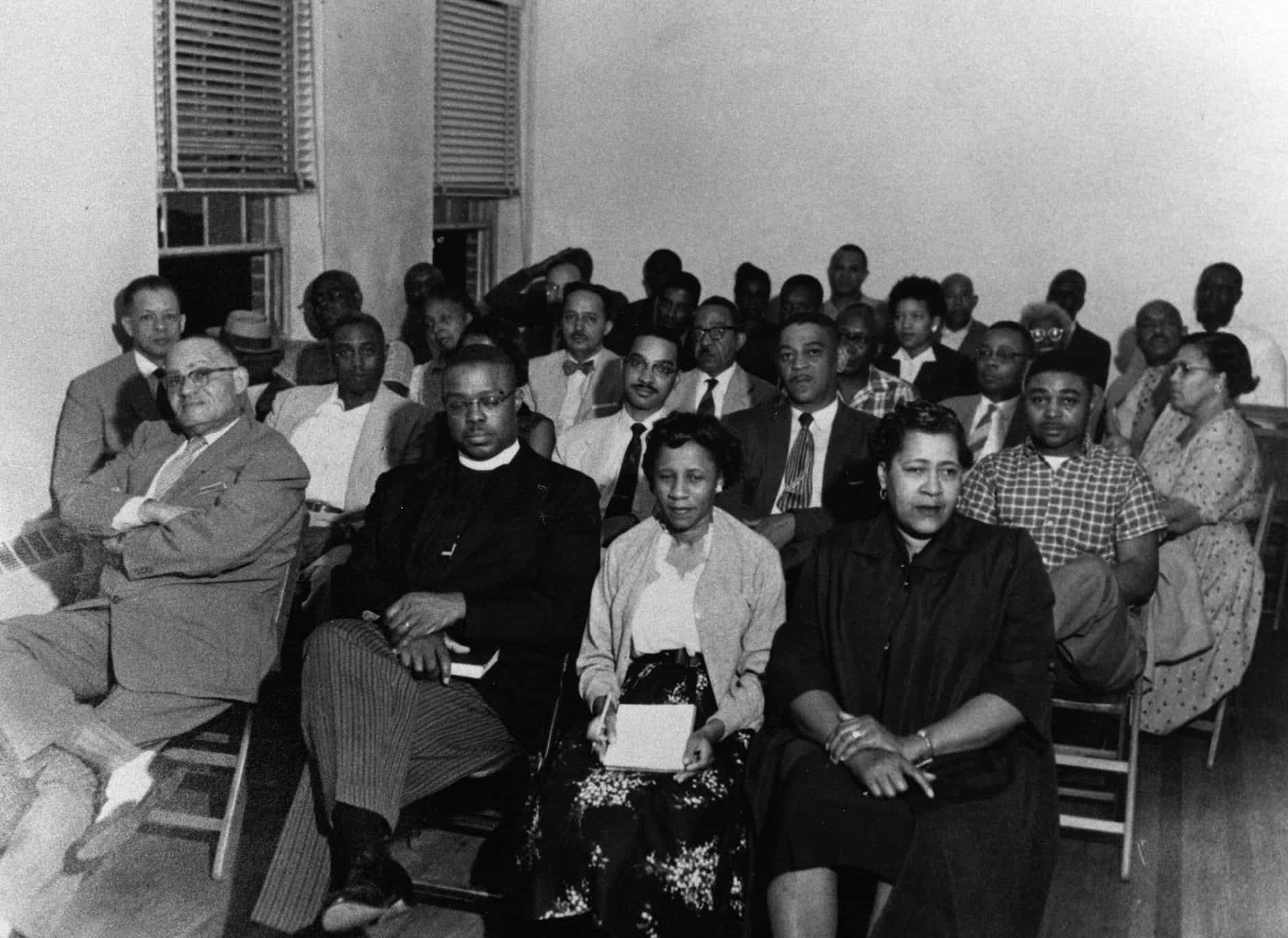

Durham Urban Redevelopment Commission members, 1960

Courtesy Durham Herald Co. Newspaper, North Carolina Collection, Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Who supported Urban renewal?

Durham City Government

- The City of Durham was the most powerful decision-maker at the table. City officials were eager to receive large amounts of money from the federal government–which was earmarked for demolition and clearance of so-called blighted areas.

- City officials believed they, not the poor themselves, had the solution to the problems facing poor neighborhoods: tear it all down and start over.

White Business Community

- White business interests were enthusiastic about building a freeway to relieve congestion downtown and connect to the newly planned Research Triangle Park.

- They also saw opportunities for private development in the clearance areas and projected an increase in the city’s tax base.

“Durham has joined an ever-growing group of American cities that are endeavoring to convert slums and blighted areas into attractive residential, commercial, and industrial areas.”

– Roy Wenzlick & Co., St. Louis based economic consultants in a report for the City of Durham, 1961

Black Leaders

- The city made three big promises to the Black community: new housing, new commercial development, and major infrastructure improvements in Black neighborhoods.

- Most working-class Black people knew little about Urban Renewal or how it would impact their lives, but voted in a bloc with the Durham Committee on Negro Affairs.

- When Urban Renewal went to public vote in a bond referendum, over 90% of Black people voted in support.

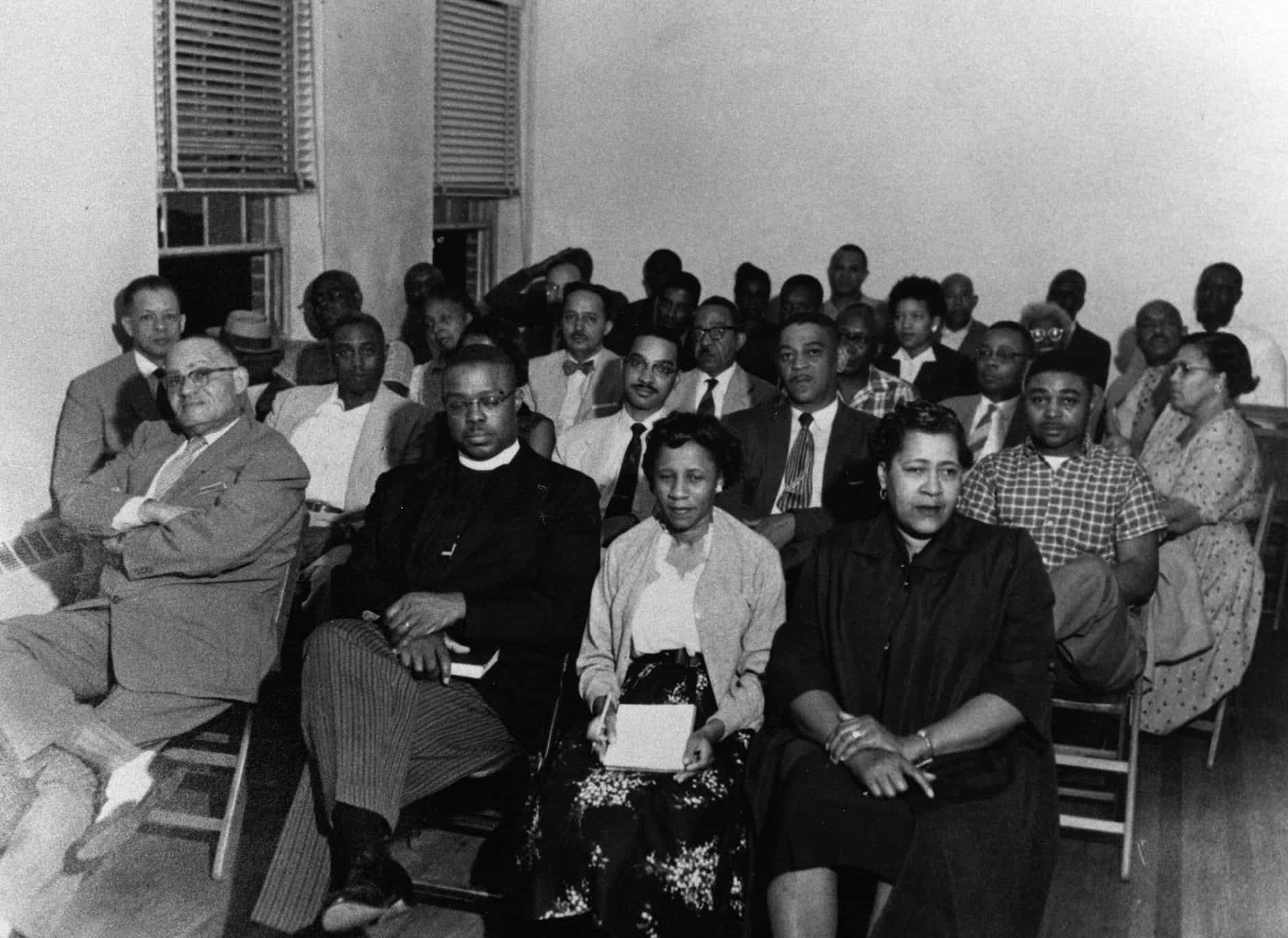

In the 1960s, Black people in Durham voted together in a bloc to maximize their political influence, guided by the advice of the Durham Committee on Negro Affairs (DNCA), pictured here. The DNCA strongly advocated in favor of the Urban Renewal bond referendum in 1963, believing it would bring long-overdue investment to Black neighborhoods.

Courtesy Durham Historic Photographic Archives,

North Carolina Collection, Durham County Library

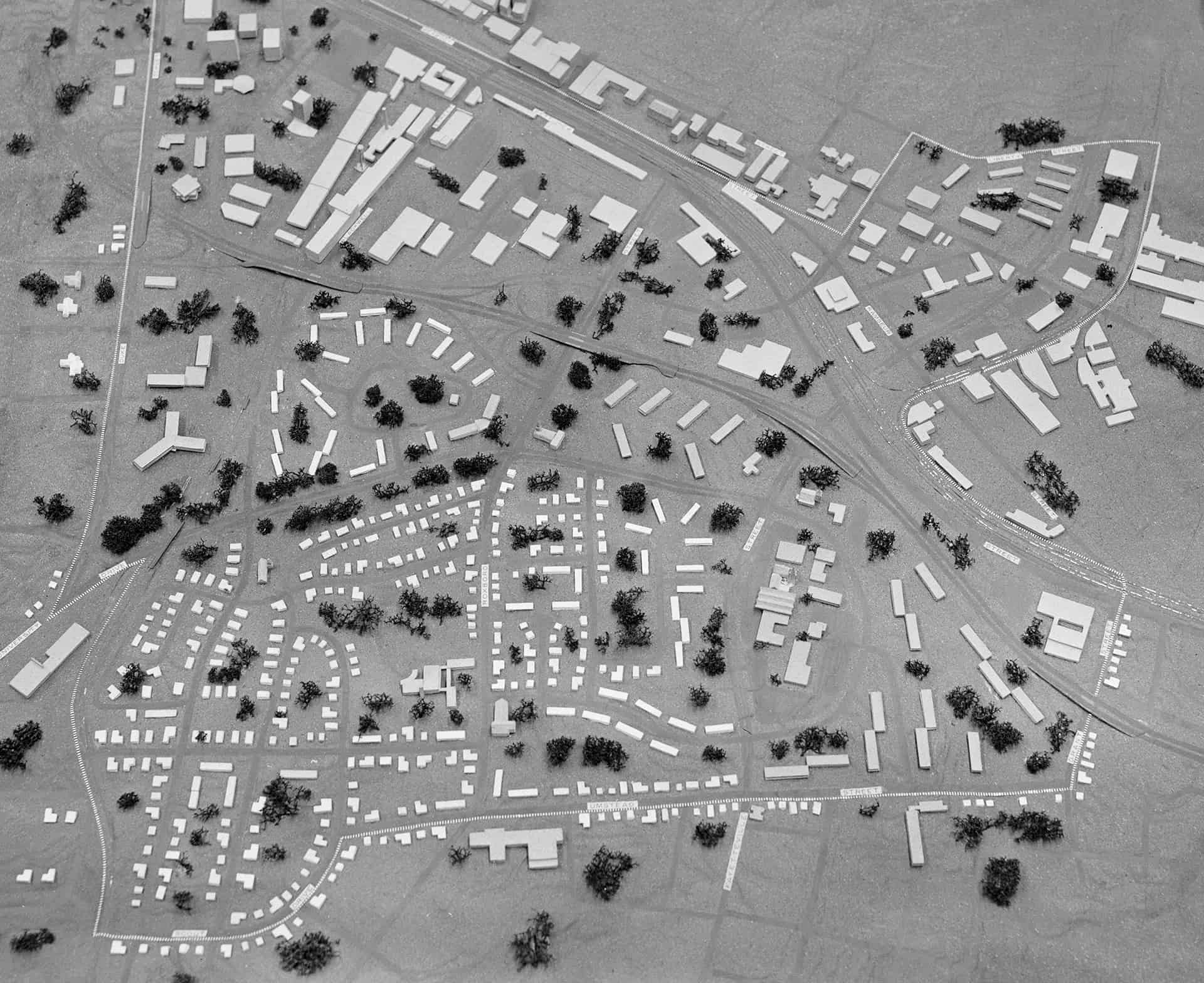

Scale model of Durham Urban Renewal redevelopment plan, circa 1963

Courtesy Durham Herald Co. Newspaper, North Carolina Collection, Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Durham Urban Redevelopment Commission members, 1960

Courtesy Durham Herald Co. Newspaper, North Carolina Collection, Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Who supported

Urban renewal?

Durham City Government

- The City of Durham was the most powerful decision-maker at the table. City officials were eager to receive large amounts of money from the federal government–which was earmarked for demolition and clearance of so-called blighted areas.

- City officials believed they, not the poor themselves, had the solution to the problems facing poor neighborhoods: tear it all down and start over.

White Business Community

- White business interests were enthusiastic about building a freeway to relieve congestion downtown and connect to the newly planned Research Triangle Park.

- They also saw opportunities for private development in the clearance areas and projected an increase in the city’s tax base.

“Durham has joined an ever-growing group of American cities that are endeavoring to convert slums and blighted areas into attractive residential, commercial, and industrial areas.”

– Roy Wenzlick & Co., St. Louis based economic consultants in a report for the City of Durham, 1961

Black Leaders

- The city made three big promises to the Black community: new housing, new commercial development, and major infrastructure improvements in Black neighborhoods.

- Most working-class Black people knew little about Urban Renewal or how it would impact their lives, but voted in a bloc with the Durham Committee on Negro Affairs.

- When Urban Renewal went to public vote in a bond referendum, over 90% of Black people voted in support.

In the 1960s, Black people in Durham voted together in a bloc to maximize their political influence, guided by the advice of the Durham Committee on Negro Affairs (DNCA), pictured here. The DNCA strongly advocated in favor of the Urban Renewal bond referendum in 1963, believing it would bring long-overdue investment to Black neighborhoods.

Courtesy Durham Historic Photographic Archives,

North Carolina Collection, Durham County Library